Judith Matz (IFAW trainee, Marine programme, EU office) updates from Song of the Whale surveying ASI blocks 25 and 26, offshore of Libya.

Sunset on the Mediterranean off the Libyan coast. We are on the tenth of many transects, navigating from east to west in a zig-zag pattern, and it is also the tenth day of our journey, following our departure from Crete, in which we survey the waters off Libya for marine megafauna. So far, most of the time, our encounters with the local fauna have been limited to shearwaters, migrating songbirds and lots of moths and butterflies, but we also spotted some striped dolphins and heard much, much more. That’s because there is a hydrophone trailing off the back of the boat on a 400-meter-long cable, and thanks to the advances of technology, we can look at and listen to the sounds it is recording on computer monitors and headphones.

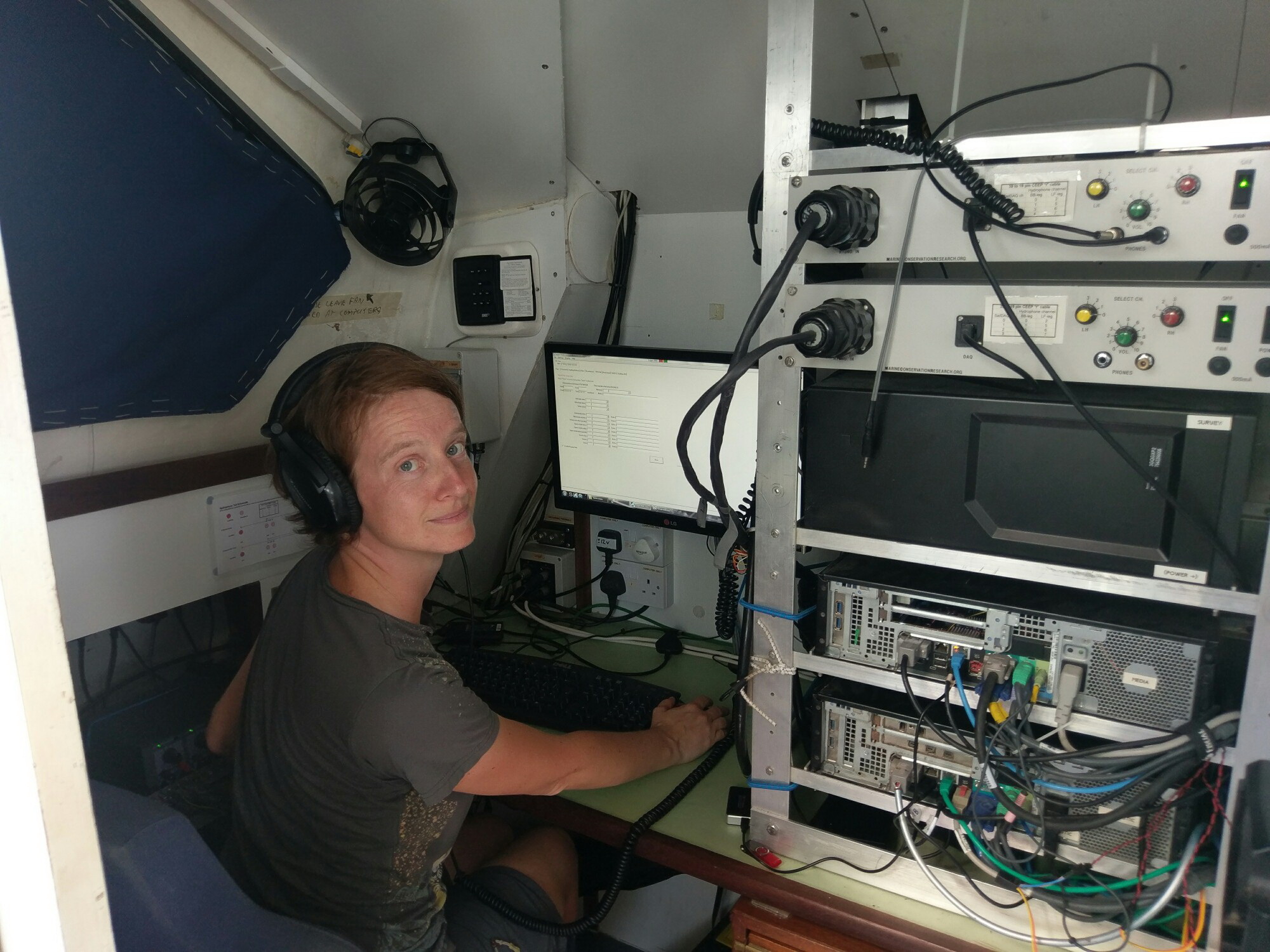

Everybody on the vessel is participating in all tasks (to varying extents): we are a mixed team of sailors, scientists, students, campaigners, from as far afield as Ireland, Libya, Spain and Germany. At all times, one person is at the helm, one is stationed at the computer, staring at data and listening to sounds, and as long as it’s light out and the wave height is not unreasonable, two people are stationed on the elevated A frame on the back deck, looking out over the sea on both sides of the boat to spot cetacean activity (but reporting mostly sightings of plastic debris).

The other day, we tracked striped dolphins and took photos of them leaping, possibly because they were trying to rid themselves of the remoras attached to them. Every now and then, the maraca-like chatter of dolphins zooms in and out of our acoustic range, and yesterday, my heart rate went up when I heard enthusiastic dolphin whistles during my two minutes of listening. A few days ago, we even tracked a submerged sperm whale whose metronome-like clicks we had picked up as it was diving deep on its hunt for squid, but alas, it got dark and so the visual search was called off.

Most of the time, we can hear the whispering of the water and the faint sound of our vessel making its way through it. Occasionally, a vessel passes by in the distance and we pick up the hum of their engine or the “woosh woosh” of the cavitation of their propeller: air bubbles building and loudly bursting due to pressure differences around the propeller blades.

After ten days, everybody has settled well into their tasks and even the rookies have figured out which lines to pull, or at least which lines not to pull. Every seven or eight hours, your number is up and you’re back on deck, day or night. We joke and tease, we fix what’s broken or work around it, we praise the dinner that a different crew member is cooking every night, and in case of boredom or confusion, the on-board scientist is happy to imitate any underwater sound we might encounter for our clarification or amusement. Even the complaints about the toilet smell have ceased now that everybody has understood the vacuum flushing system. It’s strange to think that our trip will be over in a few days’ time in the Tunisian port of Monastir.

On a project I’ve been researching for the IFAW over the summer, my attention was brought to underwater noise pollution in an investigation that was primarily focused on ship strikes and vessel speeds in the Strait of Gibraltar, the entrance to the Mediterranean from the Atlantic Ocean. Even though I’m an avid and somewhat experienced scuba diver and even though I’d like to believe that I know a little bit about the underwater world, nothing could prepare me for the barrage of noise when I put on the headphones one night while four vessels were around us on all sides. So unbearable was the noise that I could barely make it through the two minutes of listening, and I felt incredibly relieved when I could finally take off the headphones and just enjoy the (relative) silence of the world above the surface. When I reported my shock to the permanent crew members, they commented that these noises were nothing in comparison to anthropogenic noise off the coast of Portugal or in the Strait of Gibraltar. While surveying more heavily trafficked areas, listening effort must sometimes be paused in order not to hurt the ears of the team member who is listening.

While we have the luxury that we can just take our headphones off and put on our favorite song, or just listen to the wind blowing around our ears, cetaceans, and in fact any sea creature, are permanently exposed to the underwater cacophony produced by humans. Areas like the Strait of Gibraltar are heavily populated by cetaceans due to the prevalent currents providing nutrient-rich waters. At the same time, around 110 000 voyages occur in the Strait every year. That equals around 300 voyages per day or 12 per hour. I already showed signs of distress after listening to four vessels for barely two minutes. Now imagine the permanent noise level animals in the Strait of Gibraltar are exposed to. This might explain why observed potential fin whale feeding grounds in the Sea of Alboran just east of Gibraltar are bereft of the deep-diving cetaceans (Vaes et al 2013): They are too stressed by human activity to feed.

The impacts of anthropogenic noise really need to be taken seriously and effectively regulated by reducing ship speeds and implementing more efficient hull and propeller shapes for merchant and fishing vessels to keep noise to a minimum (and, hopefully, reduce ship strikes too).

Reference:

Vaes, Tom & Druon, Jean-Noel (2013). “Mapping of potential risk of ship strike with fin whales in the Western Mediterranean Sea: Potential risk of ship strike with fin whales – a scientific and technical review” JRC Scientific and Policy Reports. Report EUR 25847EN.

computer-arts.info