From the “great stink” to one of the cleanest urban rivers in the world

The River Thames is 215 miles (346 km) long and stretches from its source in Gloucestershire in the west of England, all the way out into the North Sea through the Thames Estuary. The river is tidal from Teddington Lock, in southwest London, through central London, Essex and Kent and into the North Sea. There are 47 locks and more than 100 bridges crossing the Thames.

The Thames has a great literary history, having been featured in many books, including Alice in Wonderland, The Wind in the Willows and many Charles Dickens novels, in which the Thames is described as a ‘dank stinking sludge’ and ‘the scene of murders and crime’. In the 19th Century, the ‘Great Stink’ from the River Thames was so severe that the curtains in the Houses of Parliament had to be soaked in lime to stop the bad smell from the river disrupting Government business. Between 1830 and 1860, tens of thousands of people died of cholera as a result of the pollution in the Thames.

In the 1950s the Thames was declared biologically dead due to excessive pollution from sewage and industry. It was decided that in addition to treating water abstracted from the Thames for drinking and use in homes, the dirty water flowing back into the Thames from homes and businesses should be treated at special waste water treatment plants, and new laws were put in place to discourage industry from discharging dirty water into the river. This improved people’s health as well as the health of the Thames which, despite being our busiest waterway, is now one of the cleanest metropolitan rivers in the world.

Back for good – the returning wildlife of the Thames

The Thames is now a thriving and diverse ecosystem for many species. This habitat supports 125 species of fish including eels, salmon, trout, Thames herring (also known as silver darling), over 350 species of invertebrate and even the rare sea horses. Over the last few decades, several types of mammal have returned to live in the Thames. These include otters, two types, or species, of seal, (the common seal and the grey seal), and even a small whale – the harbour porpoise.

Having a whale of a time in the Thames

From public sightings, there is evidence that whales and dolphins occasionally visit the Thames, but the UK’s smallest cetacean, the harbour porpoise, is regularly present. No scientific survey for harbour porpoises has been conducted however, and as such, we know very little about how many animals live in or move through the Thames, whether some areas particularly important to them and the threats they are facing from human activities.

Big river, small whale

The harbour porpoise is the smallest whale in Europe, measuring between 1.4 to 1.9 metres in length. They have small spade shaped teeth and are part of the odontocete family of whales (which includes dolphins, killer whales and sperm whales). Due to their small size, harbour porpoises have to feed almost continuously, on many small fish species, and occasionally squid. They are shy animals, who often avoid vessels, and are quite difficult to spot (they don’t usually jump or splash at the surface). Porpoises live throughout the North Atlantic and are most often seen in coastal habitat. Their blunt faces, dark grey bodies and small triangular dorsal fins are their characteristic features.

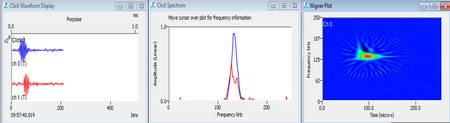

Harbour porpoises make very high pitched clicks to navigate and find their prey (this is called echolocation), as well as communicate with each other. As they are hard to see, scientists can use underwater microphones called hydrophones to pick up their clicks when porpoises are underwater. Listen to what a slowed down recording of a harbour porpoise sounds like here.